Famous Writers and Their Idiosyncrasies

Acclaimed authors are blatant about their work routines, usually obsessive, sometimes brazen and constantly distinctive. Lets take a short tour of great writers’ unusual techniques, prompts, and customs of committing thought to paper, from their ambitious daily word quotas to their superstitions to their inventive procrastination and multitasking methods.

Wallace Stevens

Manner and medium of writing seem to be a persisting theme of personal idiosyncrasy. Wallace Stevens wrote his poetry on paper slips while taking a walk— something that was a creative stimulant for him — his secretary then finished the job.

Edgar Allan Poe

Loved scrolling so much so that he attached separate pieces of paper together with sealing wax and formed it in one long school.

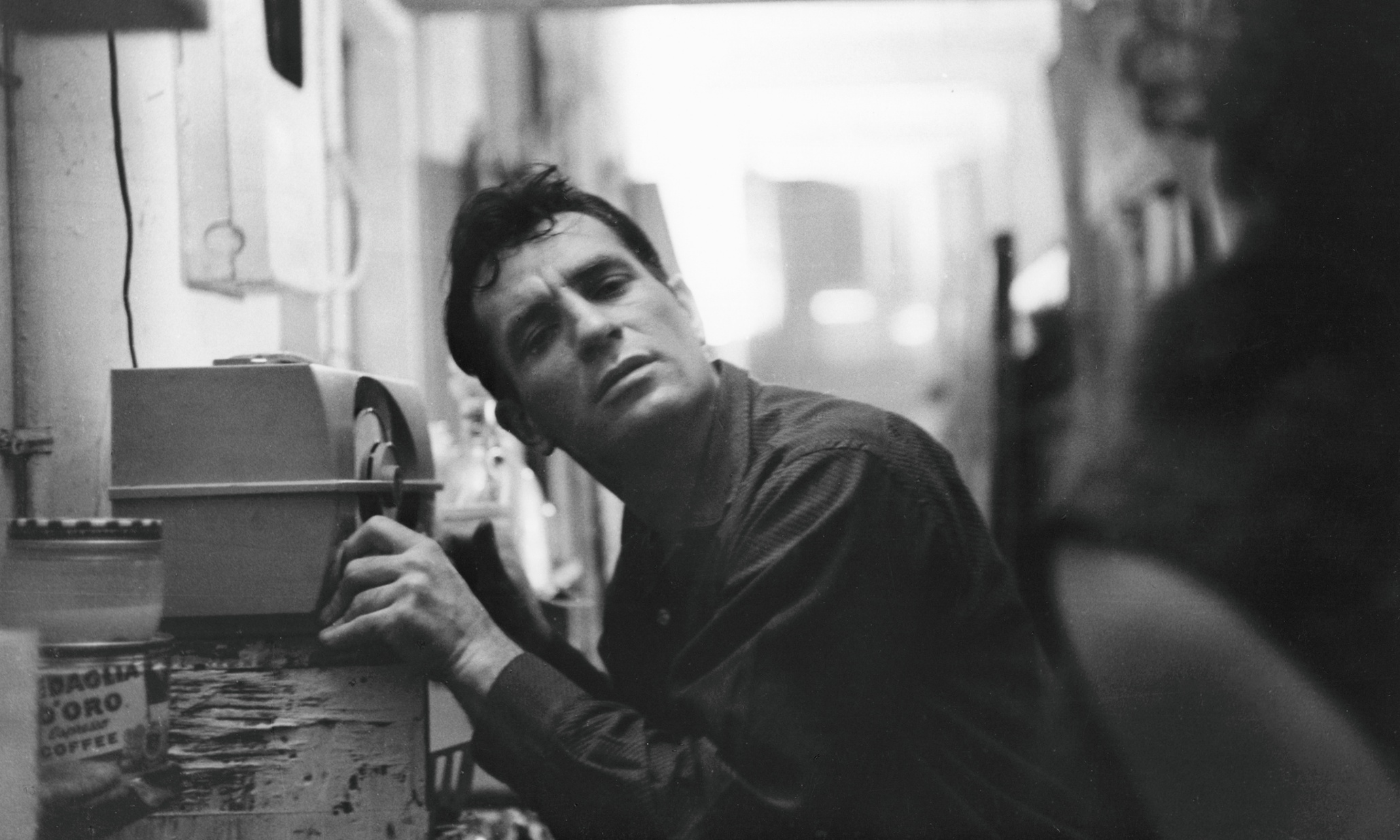

Jack Kerouac

Another writer especially partial to scrolling; In 1951, he had been planning the book for years and amassed sufficient notes in his journals, he wrote 'On The Road' in one feverish burst, pouring his soul onto paper in one long strip — a composition he believed lent itself particularly well to his project, since it allowed him to keep up his rapid pace without having to pause on order to reload the typewriter at the end of each page. After completing the manuscript he went into his editor Robert Giroux’s office and proudly spun out the scroll across the floor.

The result, however, was equal parts comical and tragic:

To his dismay his publisher's focus was on the unusual packaging and asked him to change it saying that no one could make corrections on such a manuscript. Jack left there in a huff and later found a home for his work.

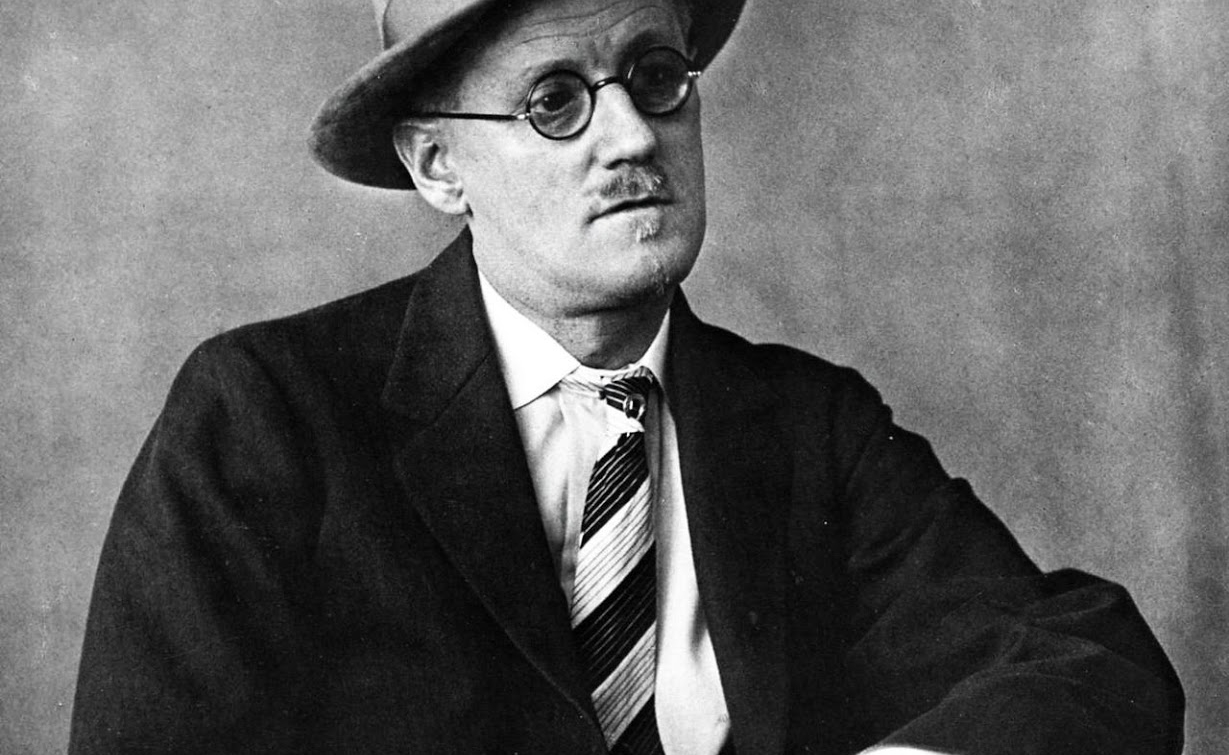

James Joyce

Wrote on his stomach in bed, with a quite big blue pencil, wearing a white coat, and wrote most of 'Finnegans Wake' with crayon pieces on cardboard. But in his case it was a matter more of practicality than of superstition or vain idiosyncrasy: Of the many outrageously misguided myths the renowned author of 'Ulysses', one who was entitled to his practice as he was nearly blind. His childhood myopia developed into severe eye problems by his twenties. The large crayons helped him see what he was writing, and the white coat reflected more light onto the page at night.

Virginia Woolf

Was as opinionated of the correct way to write as she was about the correct way to read. She spent two and a half hours each morning writing, on a three-and-half-foot tall desk with a differently made top that allowed her to look at her work both up-close and from afar. But according to her nephew Quentin Bell, Woolf’s farsighted version of the present day's podium or standing desk was less a practical matter than an outcome of sibling rivalry, the Bloomsbury artist Vanessa Bell — the same rivalry that later inspired a charming picture-book. Basically Vanessa painted standing, and Virginia didn’t want to be outdone by her sister, so she wrote standing.

Truman Capote

Some habits, of course, were far less utilitarian, leading instead to creative superstition. Capote wouldn’t begin or end a piece of work on a Friday, would change hotel rooms if the room phone number involved the number 13, and never left more than three cigarette butts in his ashtray, tucking the extra ones into his coat pocket.

Many authors measured the quality of their output by uncompromisingly perceptible metrics like daily word quotas. Jack London wrote 1,000 words a day every single day of his career and William Golding once stated at a party that he wrote 3,000 words daily, a number Norman Mailer and Arthur Conan Doyle shared. Raymond Chandler, was known to write up to 5,000 words a day at his most productive. Anthony Trollope, who began his day promptly at 5:30 A.M. every morning, habituated himself to write 250 words every 15 minutes, pacing himself with a watch.

Victor Hugo

In the fall of 1830, Hugo set out to write The Hunchback of Notre Dame against the impossible deadline of February 1831. He purchased an entire bottle of ink and put himself under house arrest by locking away his clothes and just keeping a grey shawl for himself, so that he wouldn't leave his house. He finished the book weeks before deadline, using up the whole bottle of ink to write it. He even considered titling it What Came Out of a Bottle of Ink, but eventually settled for the less abstract title.

Friedrich Schiller

The strangest habit though, comes from Schiller told by Goethe, his friend. Goethe had dropped by his house and upon seeing that Schiller was out, decided to wait for him. Rather than wasting a few spare moments, the productive poet sat down at Schiller’s desk to jot down a few notes. Then a peculiar stench prompted Goethe to pause. Somehow, an oppressive odour had infiltrated the room.Goethe followed the odour to its origin, which was actually right by where he sat. It was emanating from a drawer in Schiller’s desk. Goethe leaned down, opened the drawer, and found a pile of rotten apples. The smell was so overpowering that he became light-headed. He walked to the window and breathed in a few good doses of fresh air. Goethe was naturally curious about the trove of trash, though Schiller’s wife, Charlotte, could only offer the strange truth: Schiller had deliberately let the apples spoil. The aroma, somehow, inspired him, and according to his spouse, he “could not live or work without it.”

Agatha Christie

Most authors, of course, didn’t let their food rot for inspiration, but they were no less particular about their preferred edibles for calling upon their muse. Christie munched on apples in the bathtub while thinking up murder plots, Flannery O’Connor crunched vanilla wafers, and Vladimir Nabokov fuelled his “prefatory glow” with molasses.

Dumas, Dickens and Woolf

Then there was the colour-coding of the muses: Alexandre Dumas was also an dilettante. He penned all of his fiction on a particular shade of blue paper, his poetry on yellow, and his articles on pink; on one occasion, while traveling in Europe, he ran out of his adored blue paper and was forced to write on a cream-coloured pad, which he was convinced made his fiction suffer. Charles Dickens was partial to blue ink, but not for superstitious reasons — because it dried faster than other colours, it allowed him to pen his fiction and letters without the drudgery of blotting. Virginia Woolf used different-coloured inks in her pens — greens, blues, and purples. Purple was her favourite, reserved for letters.

In a weird way all these idiosyncrasies just inspire me to write more.